Menstrual Cycle, nutrition & training

Overview of the female menstrual cycle

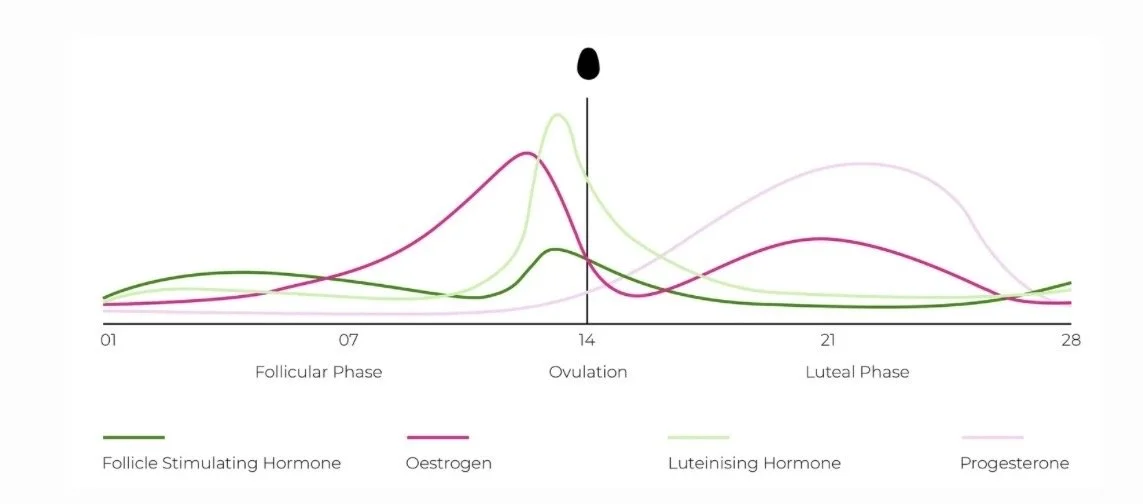

The female menstrual cycle is a monthly hormonal rhythm that prepares the body for potential pregnancy. While it is often described as a 28 day cycle, cycle length varies between individuals.

The cycle is regulated by the interaction between the brain and the ovaries, known as the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis. This axis is commonly divided into phases based on a textbook 28-day cycle:

Follicular Phase (days 1–14)

Begins on the first day of your period and ends at ovulation. This phase is characterised by rising oestrogen as ovarian follicles mature and the uterine lining rebuilds.

Ovulatory Phase (around day 14 — but this varies)!

A surge in luteinising hormone (LH) triggers the release of an egg. Ovulation itself lasts around 12–24 hours, while sperm can survive for up to five days. This is the fertile window.

Luteal Phase (days 15–28)

After ovulation, the corpus luteum forms and progesterone becomes the dominant hormone to support a potential pregnancy. If fertilisation does not occur, oestrogen and progesterone levels fall and the cycle begins again.

Fuelling Your Training & the Menstrual Cycle

Across the menstrual cycle, fluctuations in oestrogen and progesterone influence metabolism, appetite, body temperature, hunger and cravings — all of which can affect training and nutrition needs.

Because of menstruation, women are also at a higher risk of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anaemia.

Importantly, what we eat and how much we eat can influence the menstrual cycle itself. Insufficient energy intake can contribute to light, irregular, or absent periods.

During the luteal phase (the second half of the menstrual cycle), resting metabolic rate naturally increases. For some women, this rise can range from approximately 100–300 calories per day, although the extent varies widely depending on factors such as age, body composition, genetics, stress levels, illness, and overall physical activity.

The body is highly adaptive. Alongside changes in metabolism, appetite and cravings, particularly for carbohydrates and fats which often rise naturally during this phase. These signals are a physiological response.

Understanding Energy Availability

Even at rest, the body requires energy for essential processes such as breathing, circulation, digestion, and hormone production. Exercise increases these demands further.

Diet culture has often taught women to view calories as something to avoid, burn off, or “earn” through exercise. In reality, calories are simply units of energy and they are required for survival, adaptation, recovery and long-term health.

A helpful way to think about energy is as a pool. All the energy you consume goes into this pool and is used for:

Basic physiological functions

Daily movement and exercise

Recovery, repair, and hormone production

After accounting for the energy cost of exercise, the energy remaining is referred to as energy availability (EA).

If energy availability becomes too low, the body enters a state known as low energy availability. This can occur when:

Energy intake is too low

or

Training volume or intensity increases without a corresponding increase in food intake

Low energy availability is similar to putting a phone on low-power mode, non-essential functions slow down. In the body, this includes reproductive processes such as menstrual cycles, ovulation, bone health and fertility.

Before increasing training volume or intensity, it is essential to ensure that nutrition is adequate. Supplements, recovery tools, and training plans can support progress but without sufficient energy intake, hormonal disruption, injury, and burnout become more likely.

Fuel Use: Women vs. Men

Carbohydrates and fats are the primary fuels used during exercise. As intensity increases, carbohydrate use rises, while fat contributes more at lower intensities. Research indicates that women tend to rely slightly more on fat and slightly less on carbohydrates than men at the same relative exercise intensity.

A Note on Body Fat & Female Health

Females naturally carry more body fat than males, and this is both normal and essential. Body fat supports hormone production, brain and nerve function, cell health, and organ protection.

Women typically store fat in the hips, thighs, and glutes; this is an evolutionary adaptation that supports reproductive function, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. Adequate body fat is also necessary for a regular menstrual cycle; very low levels are commonly associated with cycle disruption, which is often reversible with sufficient energy intake and fat restoration.

Compared to men, women carry more subcutaneous fat and less visceral fat, a pattern that protects against cardiovascular and metabolic disease until menopause, when fat distribution becomes more central and disease risk increases.

Fuel Use Across the Menstrual Cycle

Hormonal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle may lead to small shifts in fuel utilisation, including minor changes in carbohydrate and fat use. However, these effects are modest, inconsistent, and highly individual.

Key points:

Differences in fuel use across the cycle are generally small

They are not consistent enough to justify strict phase-based training or nutrition rules

Tracking your cycle alongside energy, appetite, mood, and training performance can be helpful

Nutrition and training should always respond to how your body feels, rather than the calendar.

Luteal Phase Nutrition Considerations

For women aiming to support training and recovery, the following general considerations may be helpful — particularly during the luteal phase:

Dietary fats: Include adequate healthy fats such as avocado, nuts, seeds, olive oil, and oily fish

Protein: Prioritise protein intake to support recovery and help manage increased hunger

Carbohydrates: Under-fuelling carbs in the luteal phase can potentially worsen fatigue and cravings.

Choosing complex sources such as whole grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables can support training performance, stabilise blood sugar, manage cravings, and support moodHydration: Progesterone raises core body temperature, so fluid requirements may increase slightly

A note on cycle syncing

While awareness of the menstrual cycle can be useful, the popular concept of rigid “cycle syncing” is not strongly supported by scientific evidence. Hormonal fluctuations may influence how training feels, but differences are not consistent enough to justify broad cycle-based prescriptions.

Use your cycle as context, not a rulebook.

What You’ve Heard vs. What the Research Shows

“Women are at their best during ovulation”

Some studies suggest this; many others show no meaningful difference.“Avoid hard training during your period or luteal phase”

Performance changes are often symptom-dependent (e.g. PMS or PMDD) or influenced by perception rather than true physiological capacity.“You should only train hard 5–10 days per month”

Recent reviews show no significant effects of the menstrual cycle phase on strength, hypertrophy, or overall performance. Small reductions may occur in the late luteal or early follicular phase for some women, but these are highly individual.

The Solution: Use RPE

Rather than assuming performance will change based on cycle phase, Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) provides a practical way to auto-regulate training intensity based on how your body is responding that day.

RPE is a standardised scale validated in both endurance and resistance training. It accounts for:

Sleep quality

Nutrition and energy availability

Stress and life demands

Fatigue and recovery

Possible menstrual cycle-related symptoms

RPE for Strength Training

For resistance training, an RIR-based RPE scale (1–10) is recommended:

RPE 10 = 0 reps in reserve (maximal effort)

RPE 8 = ~2 reps in reserve

RPE 6–7 = moderate effort

This approach allows training loads to adjust naturally if energy, recovery, or symptoms fluctuate without needing to change the entire program.

RPE for Cardiovascular Training

For cardio, effort-based guidance works best. This may include:

The talk test (easy = full sentences, hard = only a few words), or

A simplified 1–10 RPE scale (easy = 3–4, moderate = 5–6, hard = 7–8)

These methods allow intensity to flex based on how you feel, rather than fixed heart-rate or calendar-based & zones.

The Bottom Line

Your menstrual cycle is a vital sign, not a strict training calendar

Cycle-related differences are not consistent enough for rigid protocols

Individual variation matters. What works one month may not the next

RPE-based training naturally accommodates daily fluctuations

Sleep, stress, nutrition, and life demands influence performance as much as hormones

Focus on consistency, adequate fuelling, and listening to your body